“A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

Hydrogen money, like hydrogen, seems all around us.

Major investments are being made in hydrogen hubs — billions of dollars in government and private equity in many regions of the U.S. and Canada. One example hub effort is the Hy Stor Energy project on the Mississippi Gulf Coast to create a massive green hydrogen production and underground hydrogen storage hub.

Senator Everett Dirksen, for whom the senate office building in Washington D.C. is named, reportedly once said, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

While the investments today are a significant down payment on a hydrogen future for North America, they are just that: a down payment. A complete hydrogen infrastructure for North America will involve trillions of dollars. There are no cheap easy fixes for replacing or repurposing the existing fossil fuel economy.

Hydrogen is complicated, as outlined in NACFE’s report Making Sense of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Tractors. Advertising by various vested interests seems to focus on the end use of hydrogen being clean and great for the environment, for jobs, for the economy and for society. Once the hydrogen is in your fuel cell car or truck, the vehicle can cleanly convert that stored molecular energy into electricity and move you down the road. The only byproduct is said to be water. That pristine view of end-use hydrogen is largely accurate, except perhaps that the water coming out is probably not quite that pure, containing some small contaminants as the fuel cells themselves degrade over time. Perhaps a minor detail fixed by filtering.

What the vested interests often fail to discuss is that the production of hydrogen is very energy intense. It doesn’t matter which color hydrogen you are discussing, breaking hydrogen free of other materials demands energy. That energy has to come from somewhere. That boundless source of energy to produce pure hydrogen for transportation and other new uses like steel, cement and other materials requires vastly increasing new energy production in North America.

That means that the proponents of hydrogen vehicles have to accept probable partnerships with nuclear power, with steam methane reformers, with coal, with oil, natural gas and more, along with green producers such as solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and others. You want a hydrogen car or truck, but are you willing to have a nuclear power plant in your neighborhood? Are you willing to share the road with more hydrogen tank trucks? Are you willing to have your view of the mountains or ocean complicated with massive wind turbines? Are you willing to financially support the fossil fuel industry to get your hydrogen? Are you willing to convert large tracts of lands to solar panels? Are you willing to help invest in carbon capture technologies to mitigate the environmental impacts of converting fossil fuels to hydrogen?

There are no easy answers. When we start down the paths of new technology we rarely have all the answers and have to discover them along the way. Innovation is like raising a baby. The idea being born is just the start. There are so many uncontrolled variables and unplanned tradeoffs in its future.

We all have grown up with gasoline and diesel-powered transportation. We depend on it. As a society, we largely accepted compromises to the environment in exchange for having increased mobility and an incredible materials production and distribution network. Since the 1970s formation of the EPA, we have been taking small steps to mitigate those compromises to claw back some of the negative ramifications of energy choices.

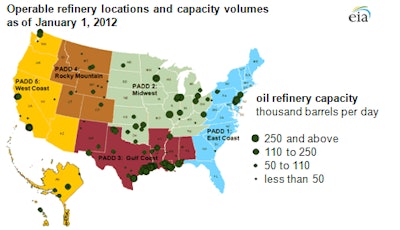

Hydrogen – the molecular vehicle fuel proposed for our future – brings with it a host of challenges, plusses and minuses. Some of the ramifications of those choices, like previous tradeoffs for diesel and gasoline, will lock in decades of compromises. A fossil fuel example is that in order to have gasoline or diesel for your vehicle, someone had to accept a refinery in their back yard in Houston or Philadelphia, pipelines everywhere, oil wells, goliath tankers sailing to and from the Middle East, and seemingly endless military investment in money and blood to secure those oil supply lines. Ignorance may be bliss, but there are no free rides; someone always pays.

Our daily lives in North America are made possible by freight movement. That freight moves today largely by fossil-fueled diesel-powered trucks, diesel-powered ships, diesel-powered trains, and oil-based jet fuel powered airplanes. The near-zero emission or true zero emission future still will require freight to be moved. That movement will require energy — a lot of new energy.

The trade-offs we will be making will be challenging to grasp. You may not care where your energy comes from or how it got to your vehicle; only that you have it available when you need it and that you can afford it. You may not care how the fuel or vehicle are subsidized to get you that energy price. Others will have a system’s perspective – the “well-to-wheel” or “mine-to-scrapyard” view of the entire energy chain.

Either way, the choices will be made and you will get energy to your vehicle. Freight will move. It will be economically and socially unacceptable to have material shortages due to an inadequate supply chain. That dissatisfaction was demonstrated in the fallout from the recent COVID pandemic supply chain challenges.

Nothing is free and there is definitely no such thing as free energy. As we start spending billions of dollars on new systems to responsibly keep our freight moving into the future, expect that tradeoffs and compromises will occur. Like our experience with gasoline and diesel over the last century, those choices will have long-term implications. Whether choosing hydrogen, battery electric or various alternative energies, put yourself 50 years in the future and ask would you have made those energy choices knowing what you now know?