The ocean shipping industry is just days away from the debut of the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), a new regulation meant to combat global warming. Even as an initial baby step, the CII is not inspiring confidence in the future decarbonization of shipping.

The new regulation seeks to lower carbon emissions by having container ships, tankers, bulkers, car carriers and other vessels operate more efficiently. It is a product of the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization (IMO) that has been in the works for years and debated ad nauseam within shipping circles.

Those outside of shipping who rely on the world’s vessels to transport their goods may scratch their heads when they learn of the strange brew the IMO has concocted. CII’s complexities, unintended consequences and weak enforcement call to mind the phrase “too many cooks in the kitchen.”

And implementation, set to begin Jan. 1, just got even more complicated.

For the CII regulation to work properly, there must be agreement between shipowners and charterers — the companies that lease ships from owners — on how the emissions-curbing responsibility is split. “Cooperation is key,” emphasized shipping insurer Gard.

The terms of that cooperation are laid out in the charter agreement or “charterparty.” A charterparty clause covering CII was finalized by shipping association BIMCO on Nov. 16.

On Tuesday, a group of the world’s largest vessel charterers sent a letter to BIMCO stating that they will refuse to use the clause because “it places the obligation to comply with CII disproportionately on charterers.” The 23 signatories included shipping lines Maersk, MSC, CMA CGM and Hapag-Lloyd; agricultural shipping giants ADM, Bunge and Louis Dreyfus; and top trading houses Trafigura and Vitol, among other big names.

How CII works on paper

The CII will assign each ship a letter rating from “A” (best) to “E” (worst) based on its annual carbon intensity in relation to an IMO-set target that will reduce over time. CII focuses on ship operations, not vessel hardware (which is the focus of a separate new regulation, EEXI).

The first CII rating will be determined in 2024, based on the carbon intensity of ship operations for the annual period starting in January. Thus, shipowner CII strategies will start affecting voyage planning very shortly.

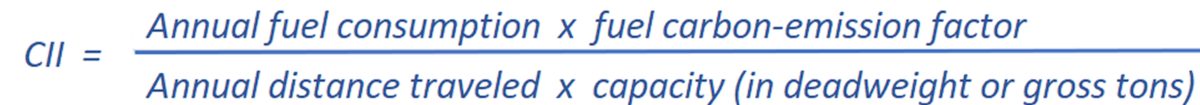

A ship’s carbon intensity is calculated by multiplying its annual fuel consumption by a carbon-emission factor assigned to the fuel type used, then dividing that total by the annual distance traveled multiplied by the ship capacity. In other words, an estimate of the carbon emissions divided by ton-miles.

What shipowners theoretically want to avoid is getting an “E” in any one year, or a “D” three years in a row. If that happens, the shipowner must update the vessel’s Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) by developing a corrective action plan, then adhere to that corrective plan.

There has been speculation that a lower rating would also make the vessel less attractive to future charterers or buyers, incentivizing owners to lower ship speed starting in 2023 and thereby lower fuel consumption to support ratings.

Unintended consequences

Numerous shipping interests have pointed to major problems with the way this regulation has been written.

“CII cannot be used to achieve desired decarbonization goals,” dry bulk shipping association Intercargo flatly asserted. “There are significant flaws.”

A central criticism is that the formula is based on ship capacity, not cargo carried, when the goal should be to reduce the carbon intensity per ton of cargo carried.

According to Oldendoff, one of the world’s largest dry bulk shipping companies, “Ship owners and operators are already trying to increase fleet productivity by reducing empty legs, so they can carry more cargoes per year.”

A bulker that carries soybeans from the U.S. Gulf to China, then picks up a load of coal in Indonesia and drops it off in Europe on its way back toward the U.S. to get more soybeans for China will emit less carbon per ton of cargo than a bulker that goes from the U.S. to China, then sails empty all the way back to the U.S. The same “triangulation” concept applies to all shipping markets.

“Even though a ship consumes more fuel during laden voyages, the improved utilization [via triangulation] decreases the emissions per ton carried, which is beneficial for the environment and should be the objective,” argued Oldendorff.

That’s not how CII works. A ship can improve its CII rating by increasing its empty ballast time, which reduces fuel consumption — but increases emissions per ton of cargo carried. “The most inefficient vessel can achieve a good CII rating by simply ballasting with no cargo,” said Oldendorff.

According to a spokesperson for MSC, the world’s largest container shipping line, “It would be far better to have an operational indicator that would reward more productive ships, including based on cargo carried rather than on a theoretical value that may not correlate to transport work performed.”

‘Slow steaming in circles’

Another criticism of CII: The equation’s denominator includes distance traveled. Thus, the shorter the distance traveled in a year, the higher (worse) the CII score.

Imagine if CII was in effect in 2021 and early 2022, when massive queues of container ships were stuck waiting off American and European ports, and hundreds of dry bulk carriers full of coal and iron ore were waiting off Chinese ports. Annual distance traveled for these vessels was severely impaired.

Port waits are usually outside the control of shipowners. The MSC spokesperson pointed out that the CII methodology “could lead to a situation in which a vessel’s rating would worsen simply because it spends more time in port.”

As Alphaliner wrote last month, “Ironically, this could lead to situations … where a vessel would be better off slow steaming in circles rather than waiting at anchor. The relatively low emissions from slow steaming are offset by additional steamed miles at an efficient ‘eco’ speed, whereas the lower emissions from anchoring are not. While such behavior could make sense to improve a ship’s rating, it is obviously counterproductive from an environmental point of view.”

Weather delays would have the same effect as port congestion, leading to lower scores for vessels deployed in regions with the worst weather (rough seas also increase fuel consumption).

In addition, there could be unintended consequences for average voyage distances, to the detriment of the environment.

According to Oldendorff, “As the CII formula uses distance in the denominator, longer voyages are favored and shorter round voyages are penalized. The likely consequence will be that less efficient ships will trend toward longer voyages, emitting more, while more efficient ships stay in the shorter trades. Meanwhile, there is no motivation to shorten trade lanes in the name of reducing emissions.”

Is CII a ‘toothless tiger’?

Then there’s the criticisms on enforcement. “We believe CII is a toothless tiger,” said Oldendorff.

What happens if a shipowner gets an “E” one year, or a “D” three years in a row, is forced to write up an action plan in its SEEMP, and doesn’t bother to follow the plan?

The IMO didn’t include enforcement measures in the regulation. “All clauses that would create consequences for noncompliance … have been removed,” wrote environmental groups in a joint statement in 2020 when the regulation was negotiated.

The IMO will review the enforcement question in 2025, but even if it agrees to add teeth, enforcement wouldn’t kick in until 2028.

Classification society DNV said, “In the meantime, we do anticipate that [failing to follow the SEEMP action plan] may have a focus with stakeholders such as flag [states], PSC [port state control], vetting and commercial parties, which may impose actions or restrictions. Whether failure to implement the SEEMP should be a detainable deficiency is still up for discussion.”

The weakness of the enforcement raises the question of how motivated some shipowners will be to comply in 2023. What if ship charterers don’t care if the vessels they lease have a “D” or an “E”?

“Neither charterers nor owners should take a hard stance on a specific CII letter rating,” maintained Oldendorff. “The ‘D’ and ‘E’ ratings are acceptable transitional ratings during the current phase of the IMO CII regulations, provided that the SEEMP improvement plan requirements are adhered to.

“If charterers insist on a higher CII rating, shipowners will need to ask for indemnification from charterers for damages to the vessel’s CII rating caused by long port stays. Similarly, owners should not worry about how their ships are traded if they are out on time charter.

“This approach will solve the problem with the BIMCO clause not being workable and end the vicious cycle where all parties seek to be indemnified for theoretical damages that can’t be quantified.”

Related articles:

- Shipping climate clash: What it means to bottom lines

- Can green shipping scheme lick ‘herding cats’ dilemma?

- Shipping decarbonization hinges on owners of cargo, not ships

- Shipping unveils blueprint for collecting future carbon tax

- Shipping’s spot-rate model could collide with green agenda

- How shipping banks’ GHG focus impacts fleets and freight rates

The post New shipping regulation to combat global warming is under fire appeared first on FreightWaves.